Nearly 100 years ago, Australian troops entered Palestine for the first time. In view of all that has happened since, it is interesting to get an outsiders view of the situation in the country at that time. The Islamic, Christian and Jewish culture had a big impact on Allan G.B. Fisher, Humphrey’s father who was on the on the Jaffa-Jerusalem road with the Australian 5th Camel Corps Field Ambulance in 1918. On his return, he wrote up his thoughts on the past, present and future of the place on his return, giving a talk on the past, present and future of Palestine and Jerusalem to the Public Questions Society of the University of Melbourne.

Nearly 100 years ago, Australian troops entered Palestine for the first time. In view of all that has happened since, it is interesting to get an outsiders view of the situation in the country at that time. The Islamic, Christian and Jewish culture had a big impact on Allan G.B. Fisher, Humphrey’s father who was on the on the Jaffa-Jerusalem road with the Australian 5th Camel Corps Field Ambulance in 1918. On his return, he wrote up his thoughts on the past, present and future of the place on his return, giving a talk on the past, present and future of Palestine and Jerusalem to the Public Questions Society of the University of Melbourne.

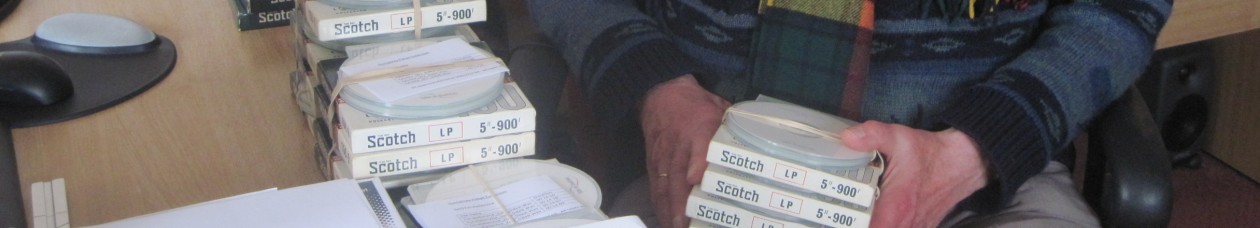

Humphrey has finished editing this talk, and is sending out copies with his Christmas letter this year, feeling it apposite in our present times. He includes a foreword, noting that despite serving in the Army, Allan wrote ‘Moreover my spirit remains entirely civilian and strongly anti-militarist’.

Whilst the first part of the talk gives some beautiful descriptions, particularly of Allan’s method of using the imagination to see history happening before his eyes, the later part contains many interesting reflections for our time, which are brought out in the Preface by his children Kate and Humphrey. Even before going to Palestine, he was

‘[on a]quest for a middle way is confirmed in his prescient Journal entries even before he enlisted. On 27 December 1914 [at age 19] he wrote:

…I am fearful of what will happen when the Allies reach German soil. The peace terms will be the greatest test. Any attempt to partition the German Empire will make this war not the last one.

Quoting from the preface, the talk is ‘capturing not only interesting local details about Palestine at a critical moment in its modern history, but also throwing light on the way in which major issues relating to the Middle East at that time might have been assessed by a perceptive contemporary observer. Indeed … at the beginning of the 21st century, the talk has many contemporary resonances:

- a war ‘to make the world safe for democracy’;

- references to the role of economic and commercial interests determining Middle Eastern policy;

- an understanding that often when the tables are turned on the former oppressors, ‘oppression and corruption, which were once detestable and iniquitous in the extreme, become natural and necessary, and are supported by all ‘right thinking’ people’.’

The talk also illustrates a range of different attitudes and assessments of Jews and Arabs, from treatment of women to the use of ‘cheap Arab labour’. While circumstances and events in the Middle East have changed dramatically over the last [100] years, the talk demonstrates that many underlying themes and issues have continued unabated, echoing eerily across the decades.

This is not to deny that the talk reflects attitudes and prejudices at the time…But at the same time, Fisher displays a respect and tolerance, coupled with a critical mind, that may have been remarkable in his day. He seeks a moderate, balanced assessment among religions, Muslim, Christian, Jewish, also between Arabs and Jews, also between Germans and the Allies. The religious balance is all the more striking because Fisher grew up in a staunch Christian family, with both parents Salvation Army officers. He was open to the ‘beauties of the faith of Islam‘, whilst being critical of Muslim attitudes towards women, for example. Perhaps the best of the Zionist movement may be illustrated by the Jews mourning at the Wailing Wall. It may be that Fisher’s admittedly sometimes selective sympathy for Islam and Judaism derived somewhat from his dissatisfaction (whatever may have been his loyalties within the family) with some of the varieties of Christianity he encountered in the Middle East. In his lecture he is sardonic about ‘the loving and fraternal Christians‘.

Descriptions of Palestine pre- British mandate

‘ A visitor to Jerusalem, a city equally venerated by Christian, Jew and Mahommedan must go there determined at all costs to see many things that are not there. … I saw Abraham and his family – this is still literally possible on every Palestinian road, – and how I watched the warriors of Joshua pursuing the Canaanite kings through the narrow Judaean valleys, the army of Sisera swept away by the ancient river Kishon, a stream which flows through the Plain of Esdraelon, a battle field scarce less famed in history than the plains of Flanders, Samson’s exploits against the Philistines, and his destruction of the great temple at Gaza, the deliverance of Andromeda by Perseus, King David dancing before the Lord as he conducted the Ark to his new and recently captured capital, Jerusalem, his flight from the city before his rebellious son, the cedars of Lebanon laboriously hauled along the coast road from Jaffa by the subject peoples of Solomon, his erection of a great palace for himself, and a temple not nearly so big for Jehovah, the armies of Egypt and Syria marching and countermarching across the territories of the unfortunate Hebrews, the busy Phoenician traders skirting along the Mediterranean coast from Tyre and Sidon, the rebuilding of the temple, the capture of Jerusalem by the army of Pompey, Galilean fishermen at work on the Sea of Tiberias, the pilgrimage of the Empress Helen, Mahommed’s miraculous journey from Mecca, the building of the Mosque of Omar, which too made Jerusalem a holy city for the Moslem world, inferior only to Mecca and Medina, the perils of the journey from Jaffa to Jerusalem in the eleventh century, the victorious progress of the first Crusaders, the Moslem children with their brains dashed out against the walls of the Holy City, the horses of the flower of European chivalry stabled in the quarries beneath the site of Solomon’s temple – now sacred to the cause of masonry – the refusal of Richard Coeur de Lion to look upon the walls of Jerusalem if he were deemed unworthy to capture the city, the overthrow of the Crusading army, maddened by thirst, at Hattin, not far from the shores of the Sea of Galilee, the unending procession of thousands of pious pilgrims from all quarters of the Christian world, the rebuilding of the wall of Jerusalem by its Turkish conquerors in the sixteenth century, the march of Napoleon and his army along the Mediterranean coast, and the 4000 Albanians shot by the French on the Jaffa beach, the conflicts between the Greek and Latin churches over the custody of the holy places, the wild scenes among the Greek pilgrims at Easter when from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre they receive what they believe to be the literal fire of the Holy Ghost – all these and many other things, though they happened at periods far remote from ours, I saw, and anyone who is to appreciate Jerusalem and Palestine must see them also.

Jerusalem

The walled city of Jerusalem is entirely mediaeval in atmosphere and appearance. The walls indeed are, as things and traditions in Jerusalem go, painfully modern, dating only from the sixteenth century…. Outside … one might imagine that he was shopping in Melbourne – the prices at least are equally high. Inside we realise at once that we are in the orient. The four quarters of the city remind the visitor that the chief reason for the existence of Jerusalem is still the essential fact that it is a religious centre. Jew, Mahommedan, Armenian, Frank divide the city between them, and it is not difficult to tell when the boundary line of each quarter has been crossed. …

From the point of view of architectural beauty, the Moslem quarter far surpasses any other in Jerusalem. This, it is true, is due entirely to the Harem esh-Sherif, the Sacred Enclosure of the Mosque of Omar, which by the way is not, strictly speaking, a mosque, and was not built by Omar. The best types of Moslem architecture have succeeded in combining simplicity and impressiveness of general design with the most delicate beauty in the details of the interior mosaic decoration. I am happily not an expert in architecture and therefore not able to bore you with expositions of Gothic and Corinthic, facades and colonnades, but unquestionably the most beautiful sight in Jerusalem is the Dome of the Rock viewed from the Temple Courtyard beneath, with cypress and olive trees in the foreground. From the point of view of architectural beauty, the Moslem quarter far surpasses any other in Jerusalem. This, it is true, is due entirely to the Harem esh-Sherif, the Sacred Enclosure of the Mosque of Omar, which by the way is not, strictly speaking, a mosque, and was not built by Omar. The best types of Moslem architecture have succeeded in combining simplicity and impressiveness of general design with the most delicate beauty in the details of the interior mosaic decoration. … Unquestionably the most beautiful sight in Jerusalem is the Dome of the Rock viewed from the Temple Courtyard beneath, with cypress and olive trees in the foreground. … The marble columns of the mosque are an impressive epitome of the history of Palestine. Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Hebrew capitals all tell the story of successive invasions of the country, the overthrow of the old religions, and the inclusion of the ruins of the old temples in the new monuments of victorious Islam.

Some of the immense stones at the base of the wall date perhaps from the time of Herod, or even of Ezra or Solomon, and here at all times, and particularly on the eve of the Sabbath, many of the Jews of Jerusalem, excluded from the spot which was once peculiarly their own, assemble to bewail the lot of their scattered brethren …. [he has] respect for many others who are there, young and old, some quietly reading the Hebrew Scriptures, others weeping silently over the long-delayed reunion of their scattered race, or passionately kissing the stones which shut them out from the ground on which once stood the Holy of Holies.

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the most renowned and most ancient of the centres of Christian pilgrimage, is so surrounded and shut in by houses and other buildings that not more than a fraction of it can be seen. …[However] even if, as was the case in 1918, the number of pilgrims in the flesh is small, it is still possible to see with the mind’s eye the myriads from all ages and countries who have filed between the narrow walls that enclose the Holy Sepulchre.

Jerusalem is not the whole of Palestine. The true Palestine is found no less in the quiet country villages and by-paths, where a twentieth-century Australian might walk for miles, without seeing anything to remind him that he was not living in the time of Solomon or of Saladin; … here [are] unmuzzled oxen treading out the corn, ploughs of the era of Abraham or of Virgil, and bricks laid out in neat rows in the sun to dry, an ox and a donkey working contentedly together beneath the same yoke, or perhaps an ox and a camel.

… In the distance a wandering tribe of Bedouins with their black tents are watching a herd of sheep and goats. A little further away is another village, inhabited not by nomadic Bedouins, but by settled Arabs … after an unbroken domicile of more than a thousand years’

Some Jews had already returned by this point, and indeed a ‘new generation of Palestinian Jews, who speak Hebrew instead of the national tongues of their fathers, who came for the most part from Russia or Roumania, many also from Germany, some from Spain and the province of Yemen, in the south Arabia, a few from America, and one lady, at least, I was told from Australia.’

Allan felt that ‘Many of the sneers which have met the Jewish Zionist ideal are undoubtedly most biased and unjust. The alleged incapacity of the Jews for agricultural or other outdoor work has, for instance, been definitely disproved, and yet it is still regularly quoted by the anti-Semites.‘ He describes ‘fertile vineyards and trim orchards’ and ‘a good picture of a small prosperous English country village in the mid-Victorian era [among the] the shady lanes on a Sabbath afternoon‘. However, ‘it is in the [ex-] Philistine plains … that the most successful results have been obtained … during the last sixty years [by the Jews]’.

Holy Sites

Fisher realises for most people living in the Middle East, their main experience of European Christian’s behaviour was the opposite of ‘loving and fraternal‘ – e.g. the need ‘for Turkish soldiers to keep the peace in Nazareth among the mixed crowds of Latin and Greek pilgrims. …

A minor point in the settlement of Palestine is the allotment of the holy places among the innumerable competing sects. As the Anglican Bishop in Jerusalem once remarked with great profundity “The question of the settlement of the holy places after the war will be not only a very difficult question -it will also be a very difficult question indeed”. This problem was one of the indirect causes of the Crimean War‘. … of course, ‘the question of the custody of the holy places does not affect the Christian sects alone’.

Future Settlement of Palestine (a view in 1919)

Allan points out the pros and cons of three options for the country, not coming conclusively down on any solution to a terribly complex situation. Clearly the most important thing was to

‘ensure the peaceful settlement of the country.’

He does not underestimate the difficulties: both moral:

‘The difficulty in Palestine, as elsewhere in the East – nor indeed is it entirely absent in countries much nearer home – seems to be that its people do not object to oppression and misrule on principle or in the abstract; the thing that does arouse their anger is their own subjection to oppression; if the tables are turned however, and instead of the Turks, the Jews or the Arabs or the Syrians or Armenians have the upper hand, oppression and corruption, which were once detestable and iniquitous in the extreme, become natural and necessary, and are supported by all ‘right-thinking’ people. I venture no opinion on the question whether this failing of human nature might be held in check by a well-constituted Jewish government, but the difficulty must be faced.’

and physical / political: ‘In the barren hills of Judaea (as opposed to the fertile plains), jests about the land flowing with milk and honey are the common property of those who have entered Palestine during recent years … the point of the joke should be directed not against the country itself, but against the peculiar methods of government which have turned so much of Palestine into a wilderness. The Judaean hills may again become fruitful and prosperous, but only under a government which will encourage the patient building up of the terraces by which alone agriculture is possible in that region. Under the Turkish rule, the methods of taxation, and the corruption of officials made thrift and careful cultivation unprofitable. The terrace-soil which needed careful attention and had taken many years to build up was washed away in a few rainy seasons, and now the terrace formation remains but it is hard and barren. This is of course far from being necessary, and there is no reason why within a measurable distance of time, Palestine should not again be capable of supporting a very large population. Even the dreaded and notorious Jordan valley – though here I speak with more reserve, as I never experienced conditions there – may again be fertilised by irrigation, and become one of the gardens of the world.‘

With lessons for the West today, he ruefully thought that ‘The importance of the question is of course not determined by the immense historical and archaeological interest of Palestine. Matters of state policy depend as a rule on something more tangible – though I should not say any more important than that, and it is the geographical position of Palestine, and the opportunities it affords for the profitable investment of European and American capital that make the settlement of the country such a live problem.’

Using irony, he gently mocked ‘the superior genius of the British people for guiding the destinies of inferior races’, adding that ‘it is extremely difficult to convince any non-British person of the existence of this inherent superiority, which is so obvious to us‘ (Allan was a New Zealander, studying in Australia).

‘Then again, it seems not unwise to note that among those who are the most enthusiastic for extensions of the British sphere of influence are the men whose financial and commercial prospects would be greatly improved by this policy. These men are perhaps high-minded idealists, whose first intent would be the well-being of the people of Palestine, and the maintenance of the peace of the world, profits being merely a secondary consideration, but it is desirable that this point should be clearly faced.’

In the words of David, revered by all three Abrahamic religions,

Let us pray for the peace of Jerusalem

and indeed of the whole Middle East.

Reblogged this on The Sound of One Hand Clapping and commented:

Wow, that is a beautiful piece of history – I am showing it to my family; we’re of Palestinian descent… – and reblogging also! Thanks. Peace x

LikeLike

Thankyou, I hope your family enjoy reading of their homeland. I read your intro; Humphrey’s wife Helga was German but born in Peru, so his family too has a mixed heritage, with many stories of refugees crossing continents, etc. Makes life more interesting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

YES! I do love a good history, especially when I hear the stories from the mouths of those who have lived them 🙂

LikeLike

I’ve just discovered that the Afghan cameleers were in Australia at the same time that Allan was riding a camel in Palestine (having travelled from Australia)!

On Monday, the SOAS Afghan Society will be joined by Dr Dawood Azami for a lecture on Australia’s Afghan Cameleers. (http://heyevent.uk/event/aavezwck6zgrwa/australias-afghan-cameleers-with-dr-dawood-azami).

He tells astonishing tales of Afghan pioneers who, with their camels, first arrived in Australia in the 1860s and criss-crossed the harsh interior of the continent for several decades & their pivotal role in the exploration and development of the continent, including laying railway lines and overland Telegraph lines…. a remarkable chapter in the history of multi-centralism.

SOAS (the School of Oriental and African Studies) is where Humphrey Fisher, Allan’s son, spent his academic career in the field of Islamic History in Africa, and supporting students in Religious Studies.

LikeLike